The History of the Museum Park Land

[[translate(episode,'title')]]

[[translate(episode,'audioCredit') || translate(episode,'credit')]][[translate(episode,'title')]]

[[translate(episode,'audioCredit') || translate(episode,'credit')]]Audio Transcript

Danny Bell, of the Lumbee and Coharie tribes of American Indians, describes how the land at the North Carolina Museum of Art would have appeared to its first American Indian settlers.

Danny Bell: “Close your eyes. And sort of tune out the cars that are going by and listen to the birds that are singing and listen to the wind blowing through the trees. Then use your smell. Smell the grass that’s growing, the flowers, the environment.”

“Most native people, if they were going to settle on a piece of land for a period of time, would’ve looked for a water source. So, you would imagine that there’s a stream running by somewhere close by, and that stream is part of the life. I mean, there might be some fish in the stream, could be some other creatures that are used for food.”

While there is no archaeological evidence that American Indians used this land, it’s likely they lived here. Because people tend to settle near water, the Park’s creek would have attracted tribes. And because this land has been heavily farmed over decades, any archaeological remains of American Indians may be lost to the ages.

From the fall of 1861 to September 1862, the area was a Civil War training camp. Camp Mangum was one of five camps in the state. An artillery battalion and 21 infantry regiments were organized and trained here. But by 1864 the state abandoned the camp, likely because they needed to rush troops into service without training.

After the Civil War, the land was used for farming and agricultural purposes, as horticulture expert Rachel Woods explains.

Rachel Woods: “The agricultural practices continued through time. When Camp Polk became Polk Prison and then Polk Youth Detention Center, the land that they had been using became property of the vet school. So, then they had cows and horses, you know. So, each kind of iteration of the different types of agriculture on the land certainly led to heavy erosion on-site.”

And one place this is most noticeable is in the Park’s stream.

Rachel Woods: “It’s really interesting to get in the stream. And the bank is kind of over your head, but you can see these layers of sediment of, it’s kind of like geologic time that you can actually see, that typically those layers are made over millennia. And in our Park, it’s been, you know, two hundred years of just bad agricultural practices.”

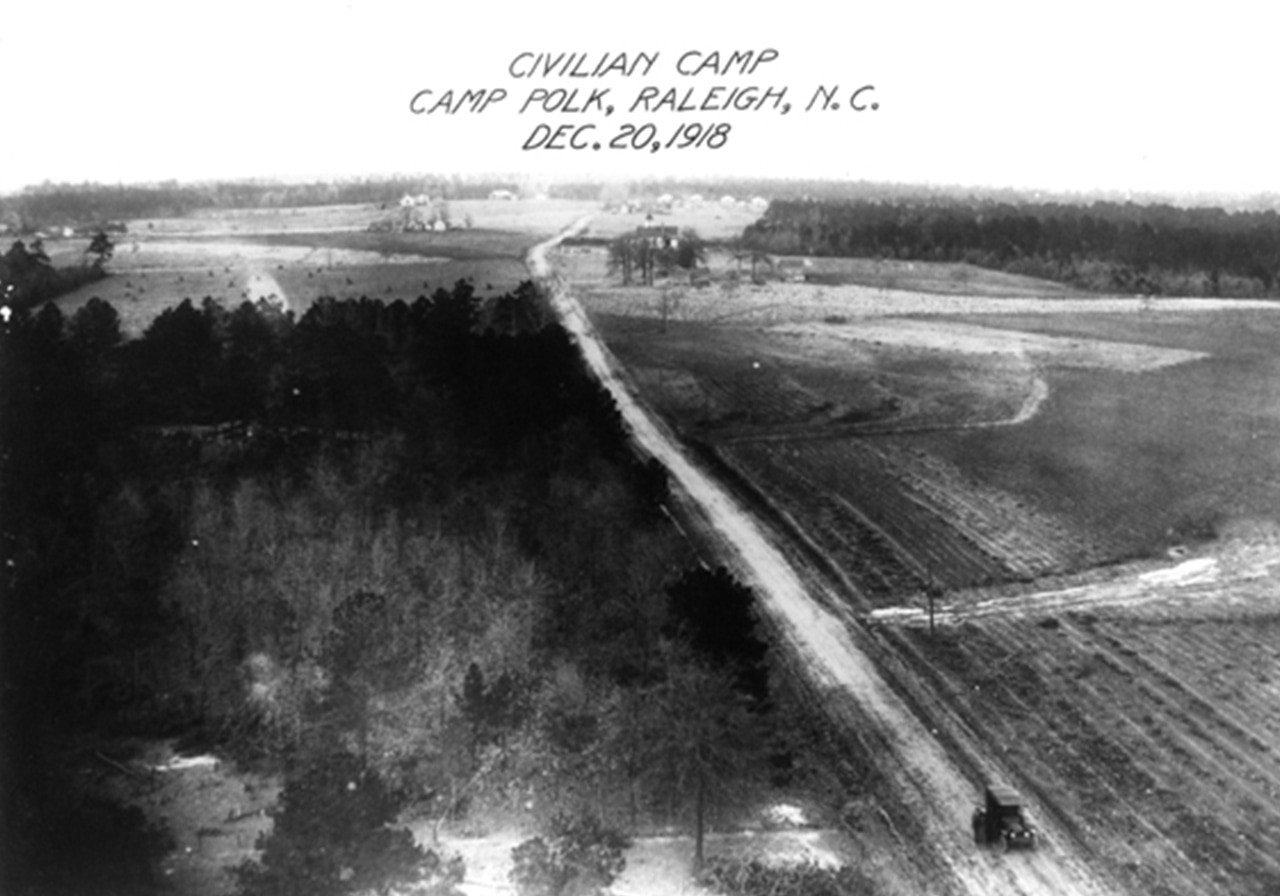

In World War I, the land became a training camp again. From August 1918 to February 1919, the US used the area as a tank training facility called Camp Polk. The name was chosen to honor North Carolina native William Polk. He was a Revolutionary War hero, Raleigh mayor, and cousin of President James K. Polk. When the war ended, the camp came to an end, but the area kept the name Polk.

By 1924 the area was Polk Prison Farm, where adult inmates worked and brought the soil back to life. The prisoners planted 250 peach trees and 250 apple trees.

The prison wasn’t without its problems. When two inmates were responsible for murders in 1959 and 1960, the public called to close the facility.

In 1963 the prison became the Polk Youth Correctional Center. It was a medium-security prison for young, male, mostly Black offenders. The original goal of the center was to give many young men the chance of a lifetime to learn a trade so they may become active contributors in the community.

When the prison moved in 1997, few were sad to see it leave. In early 2001 the land was officially transferred to the North Carolina Museum of Art, where it became the Ann and Jim Goodnight Museum Park. Museum Director Valerie Hillings explains how today’s sculpture park came to be.

Valerie Hillings: “Ann and Jim Goodnight are the most important supporters that the North Carolina Museum has had in its history, in my opinion. They committed decades ago to being really supportive of what we’re doing here in terms of the art, in terms of the Park, most especially in terms of education. They understood the potential for a park to be a big part of what this Museum is and can be. And through their support, we were able to fundamentally design the Park as an incredible experience for encountering art.”

The Park expansion opened to the public in November 2016. The renovated landscape preserved eight legacy oaks and one southern magnolia. The smokestack from the youth correctional center stands now as the lone reminder of this site’s history and a symbol of its transformation to a cultural destination for every North Carolinian.